In a startling yet expected move, Kuwait’s Emir Sheikh Meshal al-Ahmad al-Sabah in early May dissolved one of the Arab world’s few elected parliaments.

The 50-member assembly is the emblem of a democratic process which singles the country out from its regional peers. Yet, many Kuwaitis have become increasingly disillusioned with what they see as lawmakers slowing their country down.

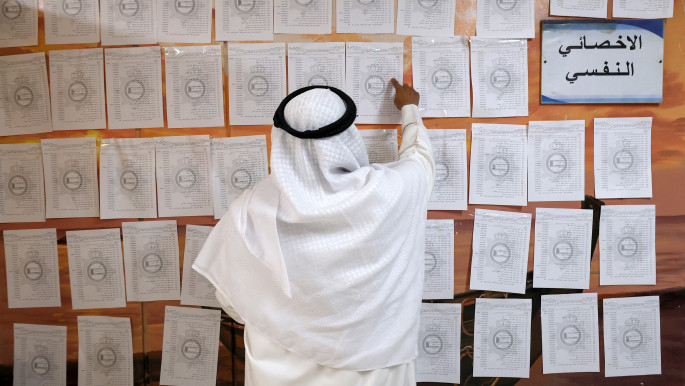

In April, Kuwait voted in its fourth parliament in as many years. The newly elected assembly, many of whom are veteran opposition lawmakers, were already threatening to “grill” a cabinet that wasn’t yet formed – a reflection of the political bickering that has mired the country’s democratic experience for decades.

“In a startling yet expected move, Kuwait’s Emir Sheikh Meshal al-Ahmad al-Sabah in early May dissolved one of the Arab world’s few elected parliaments”

“I will not allow that democracy be exploited to destroy the state,” Sheikh Meshal said on 11 May, addressing an attentive audience of about 1.3 million Kuwaitis.

Despite its riches, Kuwait is falling behind on numerous fronts. The country is an OPEC member, the Middle East’s fourth largest crude oil exporter, and has a sovereign wealth fund that owns $923 billion in assets under management.

However, the US ally, and host of multiple US military bases, has long struggled to utilise its resources to develop its services, and its plans to wean itself off its dependence on oil have seen no progress. Many attribute this to a lack of political harmony between the legislative and executive authorities, which the emir’s decision aimed to correct.

Along with suspending the parliament, Sheikh Meshal also suspended seven articles of the constitution that regulate the powers of the legislative assembly and its relationship with other authorities, for four years, during which the “democratic process will be assessed in its entirety”, and the responsibilities of the assembly will be assumed by him and the cabinet he appointed.

“We were left with no option other than taking this hard decision to rescue the country and protect its higher national interests, and resources of the nation,” the 83-year-old ruler said in his speech.

Since then, the country has been gripped by vigilance. Al-Erada Square, which has hosted countless protests over the past decade amidst political bickering and stalemates, was cordoned off as the emir read his statement. The loud political arguments which had bellowed for decades came to a halt. A few who publicly criticised the suspension were summoned by the authorities.

According to the former minister of state for national assembly affairs, Dr Abdul Hadi Al-Saleh, the move to suspend the parliament and several articles of the constitution was “not a surprise”.

“His Highness the Emir alluded to such an action on 22 June 2022, when he warned that the resumption of political tension will lead to ‘measures that will have a heavy impact and mark’,” explained Dr Saleh to The New Arab, referring to Sheikh Meshal’s speech that year following a long political feud with the government which led the cabinet to resign to avoid a no-confidence vote.

“Unfortunately, our chronic internal crises are borne by governments that do not stand up to oversight tools, and by some members of the National Assembly who compete in flogging and threatening ministers even before they assume their ministerial positions,” Dr Al-Saleh told TNA.

Chronic tensions

In the decade leading up to 2020, Kuwait recorded an average growth rate of 0.9 percent, falling behind the 2.6 percent average growth for the Middle East and North Africa region in that period.

Mega projects, like the $86 billion Silk City that is at the core of the country’s diversification plans, have been repeatedly delayed due to red tape and laws being stalled amid a political stalemate. The parliament, for example, has blocked the government from tapping into the state’s wealth fund or future generation fund.

The Mubarak Al-Kabeer Port, the cornerstone of the country’s plans to become a regional trade hub, was announced 17 years ago and was set to operate in 2019. But the $6.5 billion project has not yet been completed. Suspension of work on the port is now feared to be superseded by regional competition because of its delay.

According to Arab Barometer, a nonpartisan research network, a “striking” 66 percent of 1,210 Kuwaitis surveyed through face-to-face interviews between 14 February and 18 March said they “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed with the statement that the National Assembly had slowed down the government.

“Kuwait has long struggled to utilise its resources to develop its services, while plans to wean itself off its dependence on oil have seen no progress. Many attribute this to a lack of political harmony between the legislative and executive authorities”

However, despite the centre’s findings “that Kuwaitis acknowledge the imperfections within the country’s democratic framework” and “undeniably harbour frustration over recent parliamentary impasses, they also express a resolute endorsement” of Kuwait’s democratic heritage.

“While clashes among policymakers are normal in any democracy around the world, in Kuwait, it has harmed the country’s interests and slowed its development,” said Dr Saleh.

“This chronic and ongoing tension led to the dissolution of parliament 13 times,” since 2006, he added, noting that two previous suspensions – in 1976 and 1986 – “were in very similar circumstances” in which lawmakers were seen to have “exploited democracy and the constitution for personal gain, and stirred up hatred and misled people”.

The outcome, he noted, is “unachieved development, increased corruption rates, and dissipated stability between ministerial and parliamentary policymakers in a way that does not commensurate with Kuwait’s human and financial capabilities”.

The former minister, however, also argued that consecutive government failures to implement their development plans have provoked a “lack of wisdom” among some lawmakers.

“All these factors have come together in harming Kuwait’s democracy, which was once looked up to in the Arab world for its freedoms and achievements,” concluded Dr Saleh.

Going too far

Former minister of social affairs, Dr Ghadeer Asiri, told TNA that there have been “too many legislative deviations and practices that have been committed in the name of democracy”.

Several lawmakers have questioned or interrogated ministers for personal gain, he added, which is “far from their ministerial work or parliamentary oversight,” practices that have negatively affected the democratic process and “strayed away from the purposes it was intended for”.

Some lawmakers, emboldened by years of bickering, have also been viewed as transgressing constitutional boundaries. In a paper published in March, Associate Professor of Political Science at Temple University and Senior Fellow in the Middle East Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, Sean L. Yom, predicted a parliamentary suspension, posing the question: “Will Kuwait’s next parliament be its last?”

He cited how the last dissolution of parliament in February was triggered by a lawmaker delivering a speech deemed offensive to the Emir – a blatant breach of the constitution.

On the same note, professor of law and social policy at Kuwait University Asiri said that some parliamentarians have “blackmailed members of cabinet” through utilising “grillings to touch on ministers’ personal lives for the purpose of political exclusion,” as well as utilising social media to “attack ministers by spreading rumours and allegations that harm the national fabric and the inherent social security of the Kuwaiti home”.

Crossing such social codes, Asiri explains, “is alien to Kuwaiti society, and is a grave violation of our values,” adding that, as such, the emir’s speech and decision is “one of the steps towards correcting the flawed political process, and correcting the course for what is in the higher interest of the country”.

Restoring a state of law and values

Observers said the move, as with the two previous suspensions, is only temporary, during which laws regulating the elections and parliamentary scene are to be assessed by experts before parliamentary life is restored.

Yuree Noh, assistant professor of Political Science at Rhode Island College and Research Fellow at the Middle East Initiative at Harvard, wrote that the absence of parliamentary scrutiny is an ample opportunity for the government to “potentially implement long-awaited economic reforms and other initiatives”.

She warned, however, that “the accountability for governmental performance now rests squarely on the shoulders of the executive branch,” increasing the “pressure on the government to demonstrate effective leadership, address societal concerns, and tackle pressing challenges,” all while having to “navigate this period of political transition with diligence and transparency, aiming to rebuild public trust and steer the nation toward progress”.

According to George Emile Irani, Professor of Political Science at the American University of Kuwait, the suspension will hopefully “distance Kuwait from tribalism, sectarianism and clannism,” referring to the influence tribes have had on Kuwaiti politics through dominating the assembly.

A 2022 paper indicated that the house elected in September 2022 saw 22 lawmakers voted in from the same tribe, while the house before that, which was elected in 2020, had a record-high number of 29 members belonging to the same tribe.

In their paper, the authors explain how, on the back of years of electoral successes, “Kuwait’s tribes have become a voice of growing opposition to the royal family”, and how that success “also attracted criticisms from non-tribal Kuwaitis, who considered the tribes more loyal to their own interests than to those of the state or the wider Kuwaiti state”.

As such, Irani says that the emir’s steps were meant to protect the country’s unity, interests, and future.

“It’s to put an end to lawmakers’ misuse of their tools, and the waste of resources,” he said, noting that as the ruler goes about this “his vision of protecting the country through military and security agreements with several countries, it is important to safeguard Kuwait from within”.

This piece is published in collaboration with Egab.