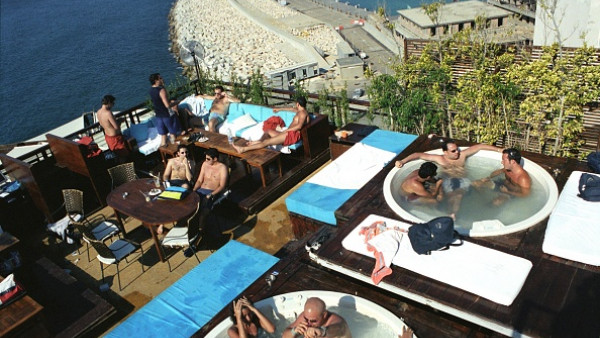

Beirut’s famous Skybar nightclub opens its doors to provide shelter to Lebanese population displaced by Israel’s attacks

Less than two weeks ago, Beirutis danced until dawn in Sky Bar, a snazzy nightclub on the Beirut waterfront. Today, families ripped away from their homes by Israel’s war on Lebanon are sleeping under its disco lights.

The world-renowned club is now home to 400 displaced people — mostly women, children, and the elderly — forced from their homes by heavy Israeli bombardment of the southern suburb of Beirut.

“It all started because our building security guards… their families and friends lost their homes in the endless bombings of Dahiyeh [the southern Beirut suburb],” Dana el-Khazen told The New Arab (TNA). Her husband, Chafic, is one of the owners of Sky Bar.

“Chafic told them [the security guards] he would open up his venue, which is Sky Bar on the roof and Skinn [nightclub] underneath, so they have a place to stay,” she said.

The displaced people have received donations of mattresses, clothing, and food through grassroots initiatives that had already sprung into action since the mass exodus from intensified Israeli attacks around Lebanon began in late September. The displaced now count over 1.2 million people, according to government figures.

“We left in the middle of the night with nothing but the clothes on our backs,” Batoul, 25, told TNA.

Sitting on makeshift beds on the floor with her mother and sister, she described the terrifying night they had to flee their home in Laylaki, a neighbourhood in the southern Beirut suburb that had also been a target of Israeli airstrikes.

‘We slept on the ground, on bare concrete’

Batoul and her family went to sleep on Friday night after one of the largest Israeli airstrikes so far during this war hit the southern Beirut suburbs, in what would later be revealed as the attack that killed Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.

“We were awakened by what felt like unending strikes — very loud, so loud we couldn’t hear each other; we had to shout. It felt like there was a thunderstorm outside,” she said.

Her family had to flee their home at 4 in the morning amidst heavy Israeli bombardment and went to the Beirut seaside promenade known as the “Corniche,” where many others who were suddenly displaced also spent the night.

“We slept on the ground, on bare concrete,” she recalled.

They returned home during the day to take showers and pray but had to leave quickly again as airstrikes resumed.

This was not the first time Batoul’s family had been displaced, however. They had left their home in Aitaroun, near the border in south Lebanon, almost a year ago, which is now the site of ground battles between Israeli troops and Hezbollah fighters.

“We have no idea if our house is still standing or not,” Wafaa, Batoul’s mother, said.

Recalling the 2006 war with Israel, which lasted 34 days, Wafaa noted that she had sought refuge in a school in Beirut, but “it was nothing like this war.”

“This time we’ve been displaced for a year; it’s not like 2006… we thought this time would be like last time, that we would go home soon.”

More than 1,900 people have been killed by Israeli strikes since the war in Lebanon began, as Hezbollah launched its “support front” for Gaza on 8 October by firing rockets into Israel.

It is unclear how many of the dead are civilians, but according to unofficial figures, around 500 Hezbollah fighters have been killed.

Wafaa has six children; two of her sons live abroad with their families. She was heartbroken when she had to say goodbye to another son on Tuesday.

“One of my sons, his family was staying in a school and left for Iraq yesterday. I cried for him and his family when I said goodbye,” she said.

“They left because they have nowhere to stay in Lebanon; the school they were staying at had no electricity or water. When I saw my grandchildren, they hadn’t showered in days,” she said tearfully. “They went by land to Syria, and then Iraq.”

Her other daughter, who is 30, sat in the corner, tears filling her eyes lined with thick black eyeliner. She was too grief-stricken to speak.

Displaced many times

Many displaced families shared similar stories of fleeing their homes in the southern Beirut suburbs after midnight due to heavy bombardment, then sleeping on the Corniche or in Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut until coming to the waterfront club.

Families sleep on thin mattresses on the floor or sofas, receive three meals a day, and have access to bathrooms and laundry facilities. Some had brought portable gas burners, pillows, blankets, and even argileh. Many of the elderly, like Sanaa, a woman in her sixties, have chronic illnesses but have access to vital medications thanks to donations received at the club.

“There is nowhere like home, but I am very grateful and thankful for the people here that took us in,” she told TNA.

Sanaa had been displaced from her home four different times due to Israeli aggression — once in the 1970s, then in 1982, in 2006, and now.

“I’m tired; this is torture… death is more honourable at this point.”

Kawthar, a middle-aged woman who was there with her husband’s extended family, said she never expected to leave her home in Burj al-Barajneh, another neighbourhood in the southern Beirut suburbs. “We have never left home in our lives; even during the [2006] July war, we stayed home for 34 days,” she told TNA.

“We were happy; we had a roof over our heads and food on our table, and then suddenly we found ourselves stranded on the streets,” she said.

Kawthar’s sister-in-law, Aya, was still in shock from all the events that had unfolded in less than a week.

“No one was expecting that Sayyed Hasan Nasrallah would be martyred,” she said, adding that she was overcome with intense grief upon hearing the news.

“The country feels broken without him [Nasrallah]; he shouldn’t have left us, but I guess this is God’s will.”

In the opposite corner of the room, a young mother, Fatima, was boiling water on a portable gas burner to prepare tea for her children.

She and her four children had been sleeping on the sidewalk in Ain el-Mreisseh when young men distributing bottles of water told them they knew of a place that could host them — a school in the Aisha Bakkar neighbourhood. After staying there for four days, she decided she had to leave again because the sound of airstrikes still terrified her children.

She was worried about her family’s future but put on a brave face for her children.

“They [her children] keep asking when they can go back home… they are terrified,” she said.

War and terror enmeshed in children’s lives

War and terror are so enmeshed in her children’s daily lives that her nine-year-old daughter can even distinguish what causes each sound coming from the sky.

“This is MK [a type of Israeli drone]; this is a sonic boom; this is an airstrike… these are some guesses my daughter makes. I wish they [her children] never had to hear any of these sounds, let alone know them well enough to distinguish [between them].”

“Before the situation escalated here, my daughter used to look at pictures and videos of children in Gaza and tell me, ‘Look, Mum, they are dying; they are under the rubble; they have nothing to eat.’ I would remind her to be grateful that she was living in peace and had food on the table.”

Unbeknownst to Fatima, she would find herself in a similar situation, with no idea if her home had been reduced to rubble or not, no idea when she would return, or what the next day would bring. All she knew was that she was sleeping in a nightclub on the Beirut waterfront.

The same Beirut waterfront that was home to many glitzy nightclubs and rooftops, representing Lebanon’s bustling nightlife and attracting tourists from around the world, now symbolises one of the worst tragedies to befall the crisis-ridden Lebanon since the 1975-1990 civil war.

(All picture credits to the author)