The need to preserve languages and dialects are a priority

Realizing dialects are not being acknowledged as official languages and are not recognized as endangered, their fate is to die silently without notice which will result in losing part of our history.

The Living Arabic Project started as a list of words on my desktop when I decided to teach myself “proper” Arabic as an adult. My interest in language started after learning a Bantu language, Shangaan or Xitsonga, while serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in South Africa, by living among the people and integrating with them rather than simply through text books. The language became beautiful and fun because of how I saw it embodied in people, and I wanted the chance to see Arabic in the same light: full of life.

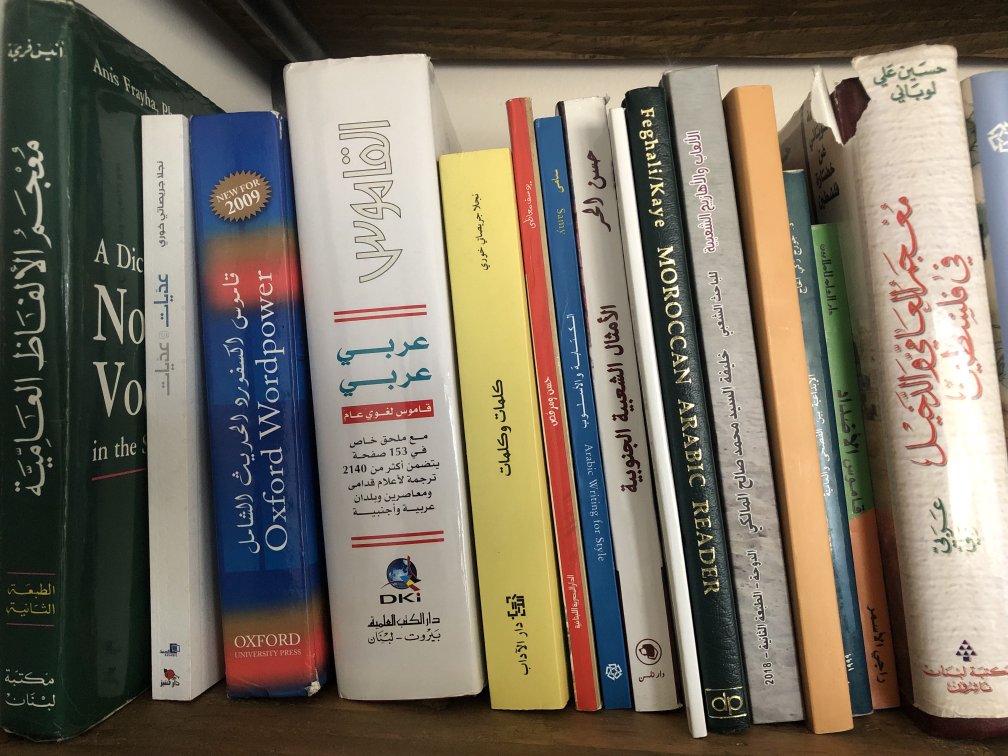

What started out as what I thought would be a simple self-education project quickly grew. I found that after a couple years of studying I had about 20,000 words in my files — 10,000 in al-Fusha and 10,000 in colloquial — and I decided to upload them in a way that users could compare the two. It became a challenge to rethink Arabic: it wasn’t just al-Fusha, and it wasn’t just my Lebanese dialect; rather al-Fusha and all the dialects seemed to me to be a huge constellation of languages. Instead of seeing the world through a monolingual framework, how could I see Arabic as a multilingual system? It took me several tries to expand the database structure enough to work properly with multiple dialects, but now the website does what it was meant to do: allow users to search in multiple dialects simultaneously and compare usages.

The project was kicked into high gear in 2015 and 2016, when a Syrian friend whom I worked with in Turkey offered to help with the coding side of the project so I could work on the language side more. He introduced me to a couple other Syrian refugees who are gifted programmers, and every year I try to raise enough money to pay them to upgrade the website and mobile apps.

Not working with dialects is also hurting our ability to pass on our language to our children. Some dialects may even disappear in the near future.

As I worked on collecting words and phrases, I realized that not only were dialects not well documented, but that not doing so was hurting us. The impact on literacy of not acknowledging dialects and helping children bridge from how they speak at home to learning al-Fusha is mind blowing. Not working with dialects is also hurting our ability to pass on our language to our children. Some dialects may even disappear in the near future. As a clear example: I’m currently working on a Gulf dictionary (for which I opened a Patreon account to raise funds), and some of those dialects only have a few hundred thousand speakers left. With many parents in the Gulf warning that their children do not speak Arabic (dialect or al-Fusha) well and instead prefer English, it seems like only a matter of time before some of these smaller dialects disappear. Moreover, because dialects are not acknowledged as official languages, they are never listed as at risk or endangered, so they will die out silently, with barely anyone noticing, but when they do we will lose a part of our history.

While I receive constant criticism of being “anti” al-Fusha, I’m quite the opposite. Al-Fusha captures a long, rich history, and cutting off Arabs from either al-Fusha or their mother dialects would be tantamount to cutting off a part of themselves. Arabic just isn’t complete without having both. Rather than see the world in binary — either al-Fusha or dialects — I believe that we can and need to work with both. The only thing stopping us is ourselves and the blind insistence on one or the other.

That original focus of the project remains the same: to see Arabic as alive. There are now multiple groups online that share words from dialects, making data available that has never been documented. Arabs in these groups often express the same sentiments that I have: that it is all Arabic, that these languages are us. It gives me hope that we can change how we look at Arabic and create a new concept of language, surpassing self-imposed limitations.

The Living Arab Project

Learn more about the Project

Written by Hossam Abouzahr

Image: Hossam Abouzahr

Publication date: January 3, 2023

Find out about nonprofits concerned with Education in the Arab World

Click to Help children, for free